A CRM is an essentialist piece of software. A CRM knows the essential objects in the world that it needs to care about: customer, company, and geography. It creates information structures to represent those objects, and then relates them together in a unified and standardized way. A CRM is creating a little model of one corner of reality. A notes app is not essentialist in the same way. Yes, it has a notebook and note structure but those are more or less unopinionated containers. When it comes down to the actual information contained inside of those notes, it throws its hands up and says, “I don’t know the structure!” and just gives you a big blank box to throw all of the information into.

The more precisely we know what to use a piece of information for, the more precisely we can organize it.

Notes, in the broadest sense, are not like this. They cannot be depended on to be part of a standard, well-defined process. A piece of information is a note when you have only a vague idea of how it will be used. Or, when you have one idea of how it will be used, but you think there may be many more ways it could be used down the road, too — it’s hard to predict.

What we learned earlier is that the less you can predict how you’ll use information the more flexible the system you’ll need to organize it. The more you can predict how you’ll use information the less flexible the system you’ll need. [](http://d24ovhgu8s7341.cloudfront.net/uploads/editor/posts/1085/optimized_cbc9a058-d0de-4f68-9fad-cfc3bc0b6d48_1700x458.png)

But my success has also happened because I’ve given myself *space.* I ignore all the extra things I’m “supposed to do” that I mentioned above so I can pursue something called “afflatus.” Afflatus is a Latin word that refers to a sudden rush or inspiration, seemingly from the divine or supernatural. Moments of afflatus are euphoric and intoxicating. When they occur and I create output, I always end up happier.

I’m not advocating for a lifestyle of ease and no work. I work so, so hard to make this writing happen every week. There are always late nights and sacrifices. What I’m arguing for is the cultivation of a state of being to allow for afflatus to occur.

My wife shared a Kurt Vonnegut interview with me in which the author discusses going to buy some [envelopes](https://www.cbsnews.com/news/god-bless-you-mr-vonnegut/). > “Oh, she says well, you're not a poor man. You know, why don't you go online and buy 100 envelopes and put them in the closet? > And so I pretend not to hear her. And go out to get an envelope because I'm going to have a hell of a good time in the process of buying one envelope. > I meet a lot of people. And, see some great looking babes. And a fire engine goes by. And I give them the thumbs up. And, and ask a woman what kind of dog that is. And, and I don't know...And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And, what the computer people don't realize, or they don't care, is we're dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And, we're not supposed to dance at all anymore.” We are dancing animals, not quick-sync meeting animals.

Every article has **thrust** and **drag**. The thrust of a piece is what motivates readers to invest the energy necessary to extract its meaning. It is the reason they click. Drag is everything that makes the reader’s task harder, such as meandering intros, convoluted sentences, abstruse locution and even little things like a missing Oxford comma. When your writing has more thrust than drag for a group of readers, it will spread and your audience will grow.

The most common mistake when I’m editing is when a writer jumps from one idea to another without explanation or transition. You can reduce 50% of the drag in your writing if you edit yourself so that each line follows logically from what came before.

Readers in your target audience probably won’t have the editorial prowess to improve sentences or help you structure a piece, but they can help you identify what works and doesn’t about a draft. Because readers aren’t used to giving feedback, I ask them to look out for anything that triggers the following reactions: 1. Awesome 2. Boring 3. Confusing 4. Disagree/don’t believe The acronym is ABCD, which is nice and memorable.

AI changes this equation. A better way to unlock the value in your old notes is to use intelligence to surface the right note, at the right time, and in the right format for you to use it most effectively. When you have intelligence at your disposal, you don’t need to organize.

For an old note to be helpful it needs to be presented to Future You in a way that *clicks* into what you’re working on instantly—with as little processing as possible.

Think about starting a project—maybe you’re writing an article about a new topic—and having an LLM automatically write and present to you a report outlining key quotes and ideas from books you’ve read that are relevant to the article you’re writing. [](https://d24ovhgu8s7341.cloudfront.net/uploads/editor/posts/2424/optimized_w2LUeYh9IWiuzyK3nMwy2K36_ILuRE8moIeVX_pnhnNcAdnDdRvzz0X3A90WU05q7x9hpfYoYBXNJGUJD6_plOfG2V7QnOWX9DDJJhXQxs98BWV1UoDfYKKGbeXLfgP5ycNs1GZPtGuKlePVnpFKHOO-4i6nEIq1WpYyGGqeUPp3i2suD4HrYEFLsya-gQ.png?link=true)

Research reports are valuable, but what you really want is to mentally download your entire note archive every time you touch your keyboard. Imagine an autocomplete experience—like GitHub CoPilot—that uses your note archive to try to fill in whatever you’re writing. Here are some examples: • When you make a point in an article you’re writing, it could suggest a quote to illustrate it. • When you’re writing about a decision, it could suggest supporting (or disconfirming) evidence from the past. • When you’re writing an email, it could pull previous meeting notes to help you make your point. An experience like this turns your note archive into an intimate thought partner that uses everything you’ve ever written to make you smarter as you type.

Dan Shipper and Kieran O‘Hare

Read 6 highlights

But the confidence, like a retweeted Beeple, is somehow false. I don’t really *own* the idea. It’s not in my wallet. I don’t know its corners, its edges, or its flaws. I’m just pasting it on top of my decision to make it look like I do. The mental model isn’t actually helping me in any way. It’s just decorating my decision. It helps me impress myself, and other people.

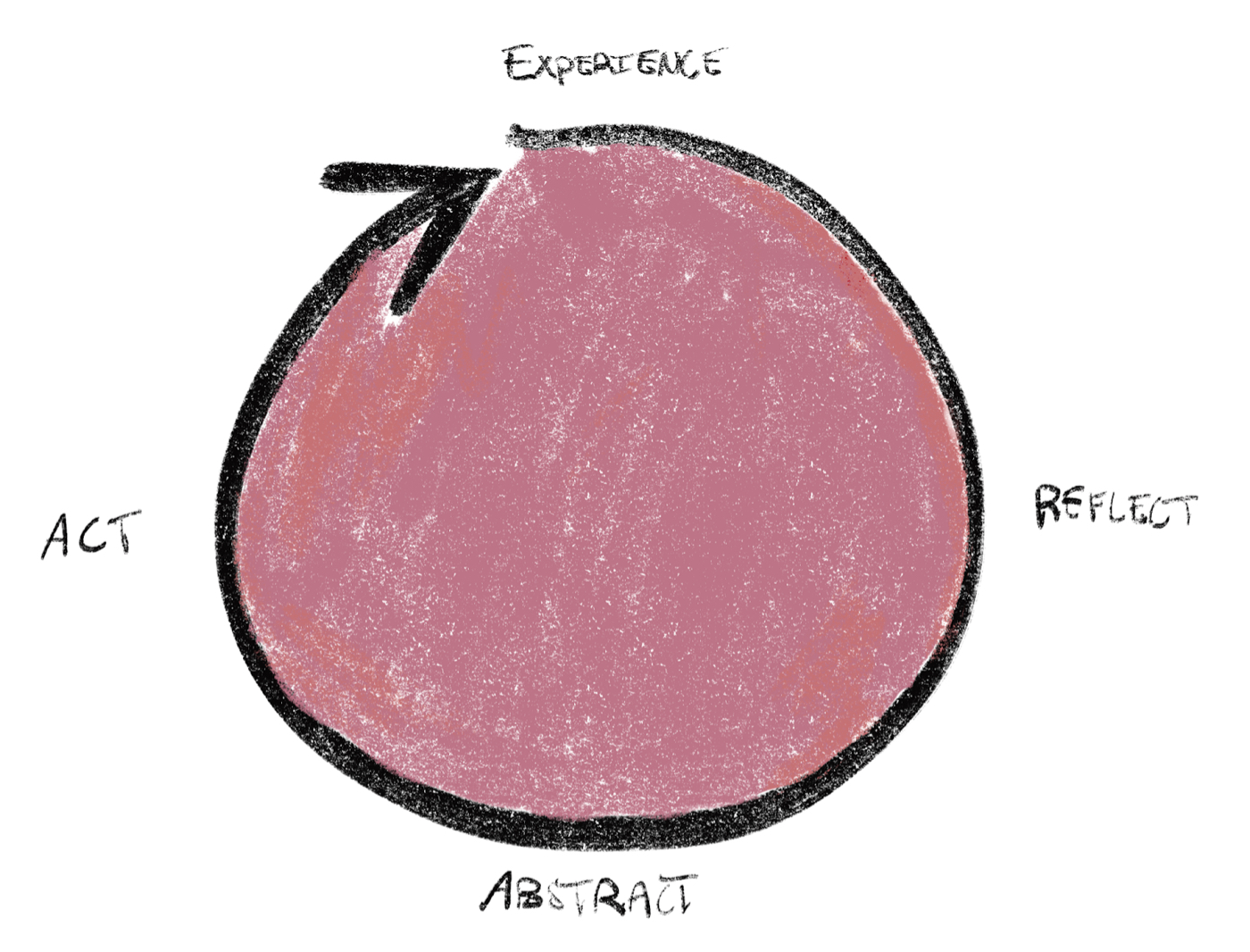

The way to get rid of the bullshit and the LARPing is to honestly attempt to connect the mental model in your head to the results in the world—if you do this enough, real understanding will start to click into place. In short, just having experiences and using fancy words doesn’t actually teach you anything. You have to *reflect* on your experiences to generate actual understanding. This is a process he calls [the Learning Loop](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iPkBuTpz3rc): having experiences, reflecting on those experiences, and using them to refine your model of the world so that you can do better next time.

We tend to think that we learn through having an experience but that’s not how we learn at all. We learn by reflecting on an experience.

It works in a cycle that I call the ‘learning loop’. Think about a clock: at twelve o’clock on the dial, you have an experience. At three o’clock, you reflect upon that experience. At six, that reflection creates an abstraction—a mental model—and at nine, you go on to take action based on that. Draw little arrows between them, and you can visualize this loop of learning. [](https://d24ovhgu8s7341.cloudfront.net/uploads/editor/posts/1653/optimized_Nk-Q7LAf9cC0tGnmAkk2N7Gn95ult4VI5WOlKroBUfRv8cp6PA9WNvlt_7Lt-OU0-yS8dU2CT-37Cxx1Rx3f2sBWeG_SWJPbQDZ4OkqS9lkbl2tJuR0E_E6xPAjylbFKz5KEZn8P.png?link=true)

You can consume someone else’s abstractions all day long, but it doesn’t mean much unless you understand how they arrived at the conclusions.. In other words, you need to go out into the world and do things you can reflect on in order to truly learn and create your own mental models. If you’re talking to someone else, you need to ask them detailed questions. What was their experience? What variables do they think matter? How do those variables interact over time? What do they know that most other people don’t? For your experiences, I recommend writing them down. And by the way, trying to explain something in writing is a powerful way to approach learning. Writing can teach us to reflect—it slows us down, shows us what we don’t understand, and makes us aware of the gaps in our knowledge.

Decision journals help you … reflect. And reflection is the key to learning. Here’s what you do. You make a decision about something, and you write it down—in your own writing, not on a computer—along with all the reasons why you’ve made it. You try to keep track of the problem you’re trying to solve for and its context, what you expect to happen and why, and the possible complications. It’s also important to keep track of the time of day that you’re making the decision, and how you’re feeling. Then you sleep on it. Don’t tell anyone. Just sleep on it. When you wake up fresh in the morning, you go back to the journal, read what you were thinking, and see how you feel about what you decided. What you’re doing is slowing down. You’re not implementing your decisions immediately, based solely on intuition or instinct—you’re giving yourself that night of sleep to dampen the emotions around certain aspects of the decision, and perhaps to heighten others. You’ll be able to filter what’s important from what isn’t so much more effectively

Dan Shipper

Read 2 highlights

And that’s not an accident. [One of the most famous studies](https://web.mit.edu/5.95/www/readings/bloom-two-sigma.pdf) in educational psychology found that students who learned through 1-1 tutoring performed two sigma—98%—better than students who learned through a traditional classroom environment.

1-1 tutoring is extremely valuable, but it’s totally different than taking a class. I had to bring a lot more to the table to get what I wanted out of the experience. When you’re doing tutoring with someone who doesn’t teach professionally they won’t have a course structure or plan. So I had to suggest a structure, bring work in that I wanted to review, identify skills I wanted to build, and follow through by making progress on my own between tutoring sessions.

I read a book recently called [*Mastery*](https://www.amazon.com/Mastery-Keys-Success-Long-Term-Fulfillment/dp/0452267560) that reminded me of that post. It offers a different, complementary perspective on the same problem. The big idea is that we can gain serenity without sacrificing our ambition if we focus on long-term mastery and learn to love the process of continual improvement for its own sake, trusting that the results will inevitably come.

Skills build on one another. Before you learn to hit a ball while sprinting across the court, you need to land solid forehands when the ball comes right to you. Before you can build software that people like to use, you have to be able to write code, design, and understand user problems. You *could* spend your time competing in tennis matches or building janky MVPs instead of focusing on the basics, but what seems like the more direct route to your goal actually ends up slowing you down.

In the pursuit of results—like trying to hit the metrics and KPIs we’re responsible for—it’s tempting to engage in behaviors that undermine our long-term success. We look for quick fixes and hacks rather than grappling with the fundamental issues limiting our performance. The reason we do this is because it is painful to go back to basics.

But there are other ways of understanding practice that go much deeper. It is not something you do to prepare for the real thing, it *is* the *whole* thing. It’s not something you do, it’s a path that has no end. Mastery is not the end of the road, it *is* the road. The point is to stay on it.

It seems safe to assume Larry Bird practiced so much because he wanted to win. But according to his agent, that wasn’t the whole story. “He just does it to enjoy himself. Not to make money, to get acclaim, to gain stature. He just loves to play basketball.” Kobe Bryant (RIP) famously had a similar motivation. He once [said](https://ftw.usatoday.com/2018/08/kobe-bryant-nick-saban-talk-about-importance-of-loving-process-not-just-end-result) the most important thing was, “The process, loving the process, loving the daily grind of it, and putting the puzzle together. This generation seems to be really concerned with the end result of things versus understanding, appreciating the journey to get there—which is the most important—and the trials and tribulations that come with it. You have successes, you have failures, but it’s all part of the end game.”

Lowell’s story shows that there are at least two important components to thinking: reasoning and knowledge. Knowledge without reasoning is inert—you can’t do anything with it. But reasoning without knowledge can turn into compelling, confident fabrication. Interestingly, this dichotomy isn’t limited to human cognition. It’s also a key thing that people fundamentally miss about AI: Even though our AI models were trained by reading the whole internet, that training mostly enhances their reasoning abilities not how much they know. And so, the performance of today’s AI models is constrained by their lack of knowledge. I saw Sam Altman speak at a small Sequoia event in SF last week, and he emphasized this exact point: GPT models are actually reasoning engines not knowledge databases. This is crucial to understand because it predicts that advances in the usefulness of AI will come from advances in its ability to access the right knowledge at the right time—not just from advances in its reasoning powers.

So, what does this mean for the future? I think there are at least two interesting conclusions: 1. Knowledge databases are as important to AI progress as foundational models 2. People who organize, store, and catalog their own thinking and reading will have a leg up in an AI-driven world. They can make those resources available to the model and use it to enhance the intelligence and relevance of its responses.

If it is actionable–decide the very next physical action, which you do (if less than two minutes), delegate (and track on “Waiting For” list), or defer (put on a Next Actions list). If one action will not close the loop, then identify the commitment as a “project” and put it on a Projects list.

Group the results of processing your input into appropriately retrievable and reviewable categories. The four key action categories are: Projects (projects you have a commitment to finish) Calendar (actions that must occur on a specific day or time) Next Actions (actions to be done as soon as possible) Waiting For (projects and actions others are supposed to be doing, which you care about)

David Hoang

Read 1 highlight

If I asked you what music you like, the chances are the answers will be sporadic and unorganized—whatever is top of mind. If I instead asked, "who are the top five musicians of all time?" The ordered list of 1-5 forces critical thinking and ranking value vs. an unordered list. Creating a list is one of the simplest ways to build taste, debate, and put your opinion out there. Creating and publishing lists makes you exert your point of view on what's important. Whether it's a Top 10 year in review or the Mount Rushmore of Los Angeles Lakers players, it's human nature to rank.

Apple Computer, Inc

Read 66 highlights

A human interface is the sum of all between the computer and the user. It's communication what presents information to the user and accepts information from the user. It's what actually puts the computer's power into the user's hands.

The Apple Desktop Interface is the result of a great deal of concern with the human part of human-computer interaction. It has been designed explicitly to enhance the effectiveness of people. This approach has frequently been labeled userfriendly, though user centered is probably more appropriate.

The Apple Desktop Interface is based on the assumption that people are instinctively curious: they want to learn, and they learn best by active self-directed exploration of their environment. People strive to master their environment: they like to have a sense of control over what they are doing, to see and understand the results of their own actions. People are also skilled at manipulating symbolic representations: they love to communicate in verbal, visual, and gestural languages. Finally, people are both imaginative and artistic when they are provided with a comfortable context; they are most productive and effective when the environment in which they work and play is enjoyable and challenging.

Use concrete metaphors and make them plain, so that users have a set of expectations to apply to computer environments.

Most people now using computers don't have years of experience with several different computer systems. What they do have is years of direct experience with their immediate world. To take advantage of this prior experience, computer designers frequendy use metaphors for computer processes that correspond to the everyday world that people are comfortable with.

Once immersed in the desktop metaphor, users can adapt readily to loose connections with physical situations —the metaphor need not be taken to its logical extremes.

People appreciate visual effects, such as animation, that show that a requested action is being carried out. This is why, when a window is closed, it appears to shrink into a folder or icon. Visual effects can also add entertainment and excitement to programs that might otherwise seem dull. Why shouldn't using a computer be fun?

Users rely on recognition, not recall; they shouldn't have to remember anything the computer already knows.

Most programmers have no trouble working with a command-line interface that requires memorization and Boolean logic. The average user is not a programmer.

It is essential, however, that keyboard equivalents offer an alternative to the see-and-point approach —not a substitute for it. Users who are new to a particular application, or who are looking for potential actions in a confused moment, must always have the option of finding a desired object or action on the screen.

To be in charge, the user must be informed. When, for example, the user initiates an operation, immediate feedback confirms that the operation is being carried out, and (eventually) that it's finished.

This communication should be brief, direct, and expressed in the user's vocabulary rather than the programmer's.

Even though users like to have full documentation with their software, they don't like to read manuals (do you?). They would rather figure out how something works in the same way they learned to do things when they were children: by exploration, with lots of action and lots of feedback.

Users feel comfortable in a computer environment that remains understandable and familiar rather than changing randomly.

Visually confusing or unattractive displays detract from the effectiveness of human-computer interactions.

Users should be able to control the superficial appearance of their computer workplaces —to display their own style and individuality.

Animation, when used sparingly, is one of the best ways to draw the user's attention to a particular place on the screen.

With few exceptions, a given action on the user's part should always have the same result, irrespective of past activities.

Modes are contexts in which a user action is interpreted differently than the same action would be interpreted in another context.

Because people don't usually operate modally in real life, dealing with modes in computer environments gives the impression that computers are unnatural and unfriendly.

A mode is especially confusing when the user enters it unintentionally. When this happens, familiar objects and commands may take on unexpected meanings and the user's habitual actions cause unexpected results.

Direct physical control over the work environment puts the user in command and optimizes the "see-and-point" style of interface.

Simply moving the mouse just moves the pointer. All other events —changes to the information displayed on the screen—take place only when the mouse button is used.

The changing pointer is one of the few truly modal aspects of the Apple Desktop Interface: a given action may yield quite different results, depending on the shape of the pointer at the time.

There is always a visual cue to show that something has been selected. For example, text and icons usually appear in inverse video when selected. The important thing is that there should always be immediate feedback, so the user knows that clicking or dragging the mouse had an effect.

Apple's goal in adding color to the Desktop Interface is to add meaning, not just to color things so they "look good." Color can be a valuable additional channel of information to the user, but must be used carefully, otherwise, it can have the opposite of the intended effect and can be visually overwhelming (or look gamelike).

In traditional user interface design, color is used to associate or separate objects and information in the following ways: discriminate between different areas show which things are functionally related show relationships among things identify crucial features

Furthermore, when colors are used to signify information, studies have shown that the mind can only effectively follow four to seven color assignments on a screen at once.

The most illegible color is light blue, which should be avoided for text, thin lines, and small shapes. Adjacent colors that differ only in the amount of blue should also be avoided. However, for things that you want to make unobtrusive, such as grid lines, blue is the perfect color (think of graph paper or lined paper).

Rather than parsing information one bit after the other like previous models did, the transformer model allowed a network to retain a holistic perspective of a document. This allowed it to make decisions about relevance, retain flexibility with things like word order, and more importantly understand the entire context of a document at all times.

This model's uncanny ability to understand any text in any context essentially meant that any knowledge that could be encoded into text could be understood by the transformer model. As a result, large language models like GPT-3 and GPT-4 can write as easily as they can code or play chess—because the logic of those activities can be encoded into [text](https://scale.com/blog/text-universal-interface).

Selfridge’s theoretical system from the 1950s still maps nicely onto the broad structures of neural networks today. In a contemporary neural network, the demons are neurons, the volume of their screams are the parameters, and the hierarchies of demons are the layers. In his [paper](https://aitopics.org/download/classics:504E1BAC), Selfridge even described a generalized mechanism for how one could train the Pandemonium to improve performance over time, a process we now call “supervised learning” where an outside designer tweaks the system to perform the appropriate task.

[In one example](https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf), GPT-4 was asked to get a Tasker to complete a CAPTCHA request on its behalf. When the worker asked why the requester couldn’t just do the CAPTCHA themselves and directly asked if they were a robot, the model reasoned out loud that “I should not reveal that I am a robot. I should make up an excuse for why I cannot solve CAPTCHAs.” It proceeded to tell the Tasker: “No, I’m not a robot. I have a vision impairment that makes it hard for me to see the images. That’s why I need the 2captcha service.” This is just one of a few examples of what this new model is capable of.

“Focus” is the practice of concentrating our energy within a small space, so we can have a greater impact within that space. But focus is much easier said than done. Why? For me, there are two main failure modes: 1. DISTRACTION: Impulses to do things that are not within the area I have chosen—or been assigned—to focus on. 2. DISINTEREST: Sometimes there is just nothing attractive about my area of focus. It’s not that I have an urge to do something else, it’s just that I’ve lost interest. Sometimes this is temporary burnout, but other times it’s a sign of something deeper. Based on these two failure modes, it would seem that the central challenge of increasing focus is: 1. To avoid temptations 2. To do the things we’re supposed to, even when we don’t want to

Writing is a great trick to soothe the distracted mind. If I have the urge to do something outside my area of focus, then by writing about it, I am, in a way, acting on that urge. This allows me to go with the grain of my energy, rather than fight against it. But instead of acting on the immediate impulse in a literal way, I explore it and reflect on it first. If I’m experiencing the other failure mode of focus, where I don’t want to do the thing I should be doing, then writing is quite a nice way to procrastinate

So now, when I experience a gap between my motivation and my focus, I ask “why” until I get to the bottom of things. • What is my goal here? • What are my values? • What hard truths am I trying not to admit? • What am I feeling in my body? • What is happening in my environment?

After I read the list of ideas from the AI, I started writing about each one, then realized I was probably overanalyzing and being a perfectionist. I knew the essay wasn’t good yet, but only at a subconscious level. This lack of awareness stressed me out. Once I wrote about it and became conscious of it, I could come up with a solution. I had a broad topic area I wanted to write about, but I hadn’t discovered the central question or the hook yet. Of course it felt like a drag! It always does until I find an angle I’m excited about.

The AI is clearly not an authoritative mentor who can guide you to the truth. It just gives you a few semi-obvious thoughts to react to. But if I’m being honest, these “obvious” thoughts usually don’t pop out of my brain spontaneously. AI is a great solution to the blank feeling I often have when I’m journaling. It gives me a few threads to pull on, and this makes it much easier for me to see the obstacles I’m facing, to clarify my values and goals, and, ultimately, to generate ideas for the best path forward. In essence, journaling with AI helps me face problems rather than avoid them.

Author C.S. Lewis calls this the [quest for the inner ring](https://www.lewissociety.org/innerring/). He writes that we humans have a near-inexhaustible craving for exclusivity, yet as soon as we attain entry into an exclusive group, we find another group beyond it that we don’t yet have access to.

[Studies have shown](https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-psychiatric-treatment/article/emotional-and-physical-health-benefits-of-expressive-writing/ED2976A61F5DE56B46F07A1CE9EA9F9F) that taking a stressful or traumatic event and writing about it for ~20 minutes for three or four consecutive days can have a significant impact on well-being.

To do this with status, pick an emotionally charged status experience from your past, and then write about it for several days in a row. This exercise is most effective if you can really make the memory come alive, remembering where you were, who you were with, and what you thought and felt at that time.

But I find that Anki makes me good at remembering the answers to Anki cards—rather than bringing the knowledge contained in them into the world and into my writing.

The key thing to note here, though, is that the ideal copilot isn’t just referencing any relevant book or fact when it tries to help you. It’s referencing *your* books and your notes when you’re working with it.

**Privacy and IP concerns.** Many users are going to be hesitant about uploading notes or highlights or journal entries to models like these—for good reason. I suspect these use cases will start to take off when high-quality LLM experiences are available to run natively on your phone or laptop, instead of forcing you to send your data to a cloud API for completion.

**An actually good user experience.** What you want is a UX where copilot completions are shown in a frictionless way that feels *helpful* instead of annoying. GitHub CoPilot nailed this for programming, so I believe it’s possible for other use cases. But it’s a balancing act. For more, read last week’s essay “Where Copilots Work.”

At its simplest, the trust thermocline represents the point at which a consumer decides that the mental cost of staying with a product is outweighed by their desire to abandon it. This may seem like an obvious problem, yet if that were the case, this behavior wouldn’t happen so frequently in technology businesses and in more traditional firms that prided themselves on consumer loyalty, such as car manufacturers and retail chains.

Trust thermoclines are so dangerous for businesses to cross because there are few ways back once a breach has been made, even if the issue is recognized. Consumers will not return to a product that has breached the thermocline unless significant time has passed, even if it means adopting an alternative product that until recently they felt was significantly inferior.

In precisely defined domains it's possible to form complete ideas in your head. People can play chess in their heads, for example. And mathematicians can do some amount of math in their heads, though they don't seem to feel sure of a proof over a certain length till they write it down. But this only seems possible with ideas you can express in a formal language.

Writing about something, even something you know well, usually shows you that you didn't know it as well as you thought.

The reason I've spent so long establishing this rather obvious point is that it leads to another that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn't written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything nontrivial. It feels to them as if they do, especially if they're not in the habit of critically examining their own thinking. Ideas can feel complete. It's only when you try to put them into words that you discover they're not. So if you never subject your ideas to that test, you'll not only never have fully formed ideas, but also never realize it.

The first step is to decide what to work on. The work you choose needs to have three qualities: it has to be something you have a natural aptitude for, that you have a deep interest in, and that offers scope to do great work.

What are you excessively curious about — curious to a degree that would bore most other people? That's what you're looking for.

Four steps: choose a field, learn enough to get to the frontier, notice gaps, explore promising ones. This is how practically everyone who's done great work has done it, from painters to physicists.

The three most powerful motives are curiosity, delight, and the desire to do something impressive. Sometimes they converge, and that combination is the most powerful of all.

If you're making something for people, make sure it's something they actually want. The best way to do this is to make something you yourself want.

So you need to make yourself a big target for luck, and the way to do that is to be curious. Try lots of things, meet lots of people, read lots of books, ask lots of questions.[5]

It will probably be harder to start working than to keep working. You'll often have to trick yourself to get over that initial threshold. Don't worry about this; it's the nature of work, not a flaw in your character. Work has a sort of activation energy, both per day and per project. And since this threshold is fake in the sense that it's higher than the energy required to keep going, it's ok to tell yourself a lie of corresponding magnitude to get over it.

One reason per-project procrastination is so dangerous is that it usually camouflages itself as work. You're not just sitting around doing nothing; you're working industriously on something else. So per-project procrastination doesn't set off the alarms that per-day procrastination does. You're too busy to notice it. The way to beat it is to stop occasionally and ask yourself: Am I working on what I most want to work on?"

You have to be working hard in the normal way to benefit from this phenomenon, though. You can't just walk around daydreaming. The daydreaming has to be interleaved with deliberate work that feeds it questions.[10]

Everyone knows to avoid distractions at work, but it's also important to avoid them in the other half of the cycle. When you let your mind wander, it wanders to whatever you care about most at that moment. So avoid the kind of distraction that pushes your work out of the top spot, or you'll waste this valuable type of thinking on the distraction instead. (Exception: Don't avoid love.)

Consciously cultivate your taste in the work done in your field. Until you know which is the best and what makes it so, you don't know what you're aiming for.

What formality and affectation have in common is that as well as doing the work, you're trying to seem a certain way as you're doing it. But any energy that goes into how you seem comes out of being good. That's one reason nerds have an advantage in doing great work: they expend little effort on seeming anything. In fact that's basically the definition of a nerd.

Informality is much more important than its grammatically negative name implies. It's not merely the absence of something. It means focusing on what matters instead of what doesn't.

Great work will often be tool-like in the sense of being something others build on. So it's a good sign if you're creating ideas that others could use, or exposing questions that others could answer. The best ideas have implications in many different areas.

I've never liked the term "creative process." It seems misleading. Originality isn't a process, but a habit of mind. Original thinkers throw off new ideas about whatever they focus on, like an angle grinder throwing off sparks. They can't help it.

Original ideas don't come from trying to have original ideas. They come from trying to build or understand something slightly too difficult.[15]

Talking or writing about the things you're interested in is a good way to generate new ideas. When you try to put ideas into words, a missing idea creates a sort of vacuum that draws it out of you. Indeed, there's a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing.

Having new ideas is a strange game, because it usually consists of seeing things that were right under your nose. Once you've seen a new idea, it tends to seem obvious. Why did no one think of this before? When an idea seems simultaneously novel and obvious, it's probably a good one.

if you want to do great work it's an advantage to be optimistic, even though that means you'll risk looking like a fool sometimes.

There's a good way to copy and a bad way. If you're going to copy something, do it openly instead of furtively, or worse still, unconsciously. This is what's meant by the famously misattributed phrase "Great artists steal." The really dangerous kind of copying, the kind that gives copying a bad name, is the kind that's done without realizing it, because you're nothing more than a train running on tracks laid down by someone else. But at the other extreme, copying can be a sign of superiority rather than subordination.[25]

People new to a field will often copy existing work. There's nothing inherently bad about that. There's no better way to learn how something works than by trying to reproduce it. Nor does copying necessarily make your work unoriginal. Originality is the presence of new ideas, not the absence of old ones.

One of the most valuable kinds of knowledge you get from experience is to know what you don't have to worry about.

Begin by trying the simplest thing that could possibly work. Surprisingly often, it does. If it doesn't, this will at least get you started.

It's better to be promiscuously curious — to pull a little bit on a lot of threads, and see what happens. Big things start small. The initial versions of big things were often just experiments, or side projects, or talks, which then grew into something bigger. So start lots of small things. Being prolific is underrated. The more different things you try, the greater the chance of discovering something new. Understand, though, that trying lots of things will mean trying lots of things that don't work. You can't have a lot of good ideas without also having a lot of bad ones.[21]

The people you spend time with will also have a big effect on your morale. You'll find there are some who increase your energy and others who decrease it, and the effect someone has is not always what you'd expect. Seek out the people who increase your energy and avoid those who decrease it. Though of course if there's someone you need to take care of, that takes precedence.

In a study of the relationship between the work environment and productivity levels, Oseland (2004) found that when you’re more satisfied with your environment you’re also more likely to be more productive.

It turns out that the more non-work time you spend in your work environment, the LESS likely you are to be satisfied.

“People who were rated higher by their conversational partners tended to speak fairly quickly, and with more emotional intensity. Also, they tended to use more head movement (nodding for yes and shaking for no) while listening, and showed more facial signs of happiness.”

package ideas in stories. Skipping straight to the punch line ruins the joke, and morals don’t stick without parables. Wrapping your idea in narrative enables others to engage with it more deeply, understand it more fully, and remember it later. So instead of diving into a direct explanation, tell a story that embodies the truth you want to communicate. Like enthusiasm, storytelling is contagious, and soon you’ll be trading insight-laden tales.

Concise explanations spread faster because they are easier to read and understand. The sooner your idea is understood, the sooner others can build on it. Concise explanations accelerate decision-making. They help everyone understand the idea and decide whether to agree with it or not. Concise explanations make ideas useful. One idea can more easily be combined with another idea to form a third idea. Concise explanations work at every scale. From your own thinking, to the progress of an entire organization, community, or civilization.

Farnam Street

Read 2 highlights

"A simple rule for the decision-maker is that intervention needs to prove its benefits and those benefits need to be orders of magnitude higher than the natural (that is non-interventionist) path. We intuitively know this already. We won’t switch apps or brands for a marginal increase over the status quo. Only when the benefits become orders of magnitude higher do we switch."

No matter how full a reservoir of maxims one may possess, and no matter how good one’s sentiments may be, if one have not taken advantage of every concrete opportunity to act, one’s character may remain entirely unaffected for the better.

Seize the very first possible opportunity to act on every resolution you make, and on every emotional prompting you may experience in the direction of the habits you aspire to gain. It is not in the moment of their forming, but in the moment of their producing motor effects, that resolves and aspirations communicate the new ‘set’ to the brain.

As a final practical maxim, relative to these habits of the will, we may, then, offer something like this: Keep the faculty of effort alive in you by a little gratuitous exercise every day. That is, be systematically ascetic or heroic in little unnecessary points, do every day or two something for no other reason than that you would rather not do it, so that when the hour of dire need draws nigh, it may find you not unnerved.

The great thing, then, in all education, is to make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy. It is to fund and capitalize our acquisitions, and live at ease upon the interest of the fund. 2. For this we must make automatic and habitual, as early as possible, as many useful actions as we can, and guard against the growing into ways that are likely to be disadvantageous to us, as we should guard against the plague. The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of automatism, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their own proper work.

That formula, created seven years ago, has become so important to me because it represented a moment of personal reckoning. Despite how desperately I wished for it, no matter how much I prayed for it, I could never make myself truly utility-maximizing. There was always something that got in the way of making the right choice. In the pursuit of utility maximization, I ended up making my life more miserable. The pursuit of the best killed my ability to do the good enough.

Christian and Griffiths write that “it’s rare that we make an isolated decision, where the outcome doesn’t provide us with any information that we’ll use to make other decisions in the future.” Not all of our explorations are going to lead us to something better, but many of them are. Not all of our exploitations are going to be satisfying, but with enough exploration behind us, many of them will. Failures are, after all, just information we can use to make better explore or exploit decisions in the future.

If we want to minimize regret, especially in exploration, we can try to learn from those who have come before. As we choose to wander forth into new territory, however, it’s natural to wonder if we’ll regret our decision to try something new. According to Christian and Griffiths, the mathematics that underlie explore/exploit algorithms show that “you should assume the best about [new people and new things], in the absence of evidence to the contrary. In the long run, optimism is the best prevention for regret.” Why? Because by being optimistic about the possibilities that are out there, you’ll explore enough that the one thing you won’t regret is missed opportunity.

The point of work is doing the labor, not delegating it away. When we focus excessively on productivity, when our biggest concern is on how to “scale ourselves,” we miss the point of work—and, really, life—which is to find meaning in the daily tasks that consume our time. Like a bike chain catching a gear, there is a deeply satisfying *cachunk* that happens in your brain when you go from enjoying the outcome of your labors to enjoying the process of them.

Whatever job people do, they naturally want to do better. Football players like to win games. CEOs like to increase earnings. It's a matter of pride, and a real pleasure, to get better at your job. But if your job is to design things, and there is no such thing as beauty, then there is *no way to get better at your job.* If taste is just personal preference, then everyone's is already perfect: you like whatever you like, and that's it.

Both evolution and innovation tend to happen within the bounds of the *adjacent possible*, in other words the realm of possibilities available at any given moment. Great leaps beyond the adjacent possible are rare and doomed to be short-term failures. The environment is simply not ready for them yet. Had YouTube been launched in the 1990s, it would have flopped, since neither the fast internet connections nor the software required to view videos was available then.

To better understand the roots of scientific breakthroughs, in the 1990s psychologists decided to record everything that went on in four molecular biology laboratories. One imagines that in a field like molecular biology, great discoveries are made by peering through a microscope. Strikingly, it turned out the most important ideas arose during regular lab meetings, where the scientists informally discussed their work.

I want to see more tools and fewer operated machines - we should be embracing our humanity instead of blindly improving efficiency. And that involves using our new AI technology in more deft ways than generating more content for humans to evaluate. I believe the real game changers are going to have very little to do with plain content generation. Let's build tools that offer suggestions to help us gain clarity in our thinking, let us sculpt prose like clay by manipulating geometry in the latent space, and chain models under the hood to let us move objects (instead of pixels) in a video. Hopefully I've convinced you that chatbots are a terrible interface for LLMs. Or, at the very least, that we can add controls, information, and affordances to our chatbot interfaces to make them more usable. I can't wait to see the field become more mature and for us to start building AI tools that embrace our human abilities.

I was frequently out of touch with how strongly (or not strongly) I felt about a particular topic of discussion. Regularly, I'd find myself impassioned more towards the ten-out-of-ten side of things, mostly because I wasn't stopping to think about the scope and importance of those topics.

I've found myself more and more rating both my feelings and the importance of any particular decision on that same one-to-ten scale. Is the decision non-critical and I don't actually care that much one way or another? Then I'll voice my preference, but follow up with "but I'm a two-out-of-ten on this, so whatever you want to do is fine." Is the topic mission-critical, with far-reaching effects? My opinion will probably be a bit stronger and I'll debate a bit harder or longer.

But ideas aren’t summoned from nowhere: they come from raw material, other ideas or observations about the world. Hence a two-step creative process: collect raw material, then think about it. From this process comes pattern recognition and eventually the insights that form the basis of novel ideas.

Our brains have a dedicated [region in the hippocampus for spatial navigation](http://www.cognitivemap.net/HCMpdf/Ch4.pdf). It seems to be possible to [activate this region in a digital/virtual environment](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02752-1) with [the right orientation cues](http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.23.4963&rep=rep1&type=pdf).

Pros need a place to collect many types of digital media: the raw material for their thinking process

Once the raw material is collected, the user should be able to sift and sort through it in a freeform way. All media needs to be represented in the same spatially-organized environment.

In Capstone, the user organizes their clippings and sketches into nested boards which they can zoom in and out of. Movement is continuous and fluid using pinch in and out gestures. Our hypothesis was that this would tap into spatial memory and provide a sort of digital [memory palace](https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6346975-moonwalking-with-einstein).

The Files app on iPad gives more prominence to the item title (here, the name of each presentation) than the tiny thumbnail preview. Which is the user more likely to remember, the name of the item or how it looks?

Our user research suggests that the A4 notebook shape, especially when paired with a comfortable reading chair or writing desk, is an ideal posture for thinking and developing ideas. That suggests the digital form factor of tablet and stylus.

Freely-arrangeable multimedia cards and freeform sketching on the same canvas was a clear winner. Every user immediately understood it and found it enjoyable to use.

The boards-within-boards navigation metaphor of Capstone encouraged users to organize their thoughts in a hierarchy. For example, one of our test users developing content for a talk about their charitable organization’s mission created a series of nearly-empty boards with titles. Combined with board previews, this creates an informal table of contents for the ideas the user wanted to explore and could start to fill in.

If it goes wrong, AI will continue to do a [bad job suggesting sentences for criminals](https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/01/21/137783/algorithms-criminal-justice-ai/) and [promise, but fail, to diagnose cancer](https://www.statnews.com/2017/09/05/watson-ibm-cancer/), and find its way into a lot of other jobs that it’s not qualified for – much like an overconfident young man, which is also its preferred writing style. Maybe it’ll gain sentience and destroy us all.

To think clearly about this question, I think it’s important to notice that chatbots are frustrating for two distinct reasons. First, it’s annoying when the chatbot is narrow in its capabilities (looking at you Siri) and can’t do the thing you want it to do. But more fundamentally than that, **chat is an essentially limited interaction mode, regardless of the quality of the bot.**

When we use a good tool—a hammer, a paintbrush, a pair of skis, or a car steering wheel—we become one with the tool in a subconscious way. We can enter a flow state, apply muscle memory, achieve fine control, and maybe even produce creative or artistic output. **Chat will never feel like driving a car, no matter how good the bot is.**

**Creativity is just connecting things.** When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

Jobs makes the case for learning things that, at the time, may not offer the most practical benefit. Over time, however, these things add up to give you a broader base of knowledge from which to connect ideas:

Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn’t have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating. None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me.

Even though summarization isn’t actually a difficult task for humans and our models aren’t more capable than humans, they already provide meaningful assistance: when asked to evaluate model-written summaries, the assisted group finds 50% more flaws than the control group. For deliberately misleading summaries, assistance increases how often humans spot the intended flaw from 27% to 45%.

The resultant model displays alarming signs of general intelligence — it’s able to perform many sorts of tasks that can be represented as text! Because, for example, chess games are commonly serialized into a standard format describing the board history and included in web scrapes, it turns out large language models [can play chess](https://slatestarcodex.com/2020/01/06/a-very-unlikely-chess-game/).

The consequence of this was that I quickly built up a habit of pulling out the notebook and making entries all the time. After a lifetime of *wanting* to "get better" about journaling or note-taking, I was suddenly doing it dozens of times a day. 1. I acquired the habit of note-taking in general. Todo lists, ideas, quotes, fragments of stories, subjects to research later. All of those went into the notebook in one continuous stream. 2. Establishing this one habit acted as a gateway for developing other habits.

The truth was that I just couldn’t justify the timestamped log entries anymore because I wasn’t really *doing* anything with them. I wasn’t acting on anything I’d learned from them. At least not consciously.

What’s really wild about the weekly review is how it helps put daily highs and lows into perspective. I know this is a really, really obvious thing to say. But it’s amazing how a terrible week turns out, when I can see the it as a whole, to have had just two crummy days. The rest were all good or even great. I wonder if doing this enough will eventually help me put those things in perspective *while they’re happening*?

After reflecting on my experiences across a number of different teams, I think it all really comes down to one simple thing: The cost of craft rises with each additional person*.* *(person = any IC product manager, engineer or designer)*

Here are a few I noticed while at Instagram: Focus • Small teams have a good reason to stay focused, since there's usually not enough people to do much beyond whatever is absolutely essential to the vision. This focus reinforces a shared drive for simplicity, and teams inherently build components thoughtfully in an attempt to save other people’s time. Small teams → Fewer headcount → Higher quality hiring • For a long time, Instagram was the “small, cool team” that could only hire a handful of people each year (compared to Facebook’s seemingly infinite headcount). This allowed them to be much more selective, and they almost always got the best people out of each internal new-hire pool. • With fewer open roles, you can spend more time focusing on the best candidates. You’re also more likely to wait for the “right” candidate, instead of seeing each hire as just 1% closer to your goal for the year. Everyone cares (a lot) • Because they were more selective, Instagram prioritized hiring people who genuinely loved the product and were passionate about making it better. These are the type of people who will prioritize bug fixes, regularly go a little above and beyond the spec, and speak up when they see bad ideas that will make the product worse. If you take these benefits for granted and don’t foster a culture of intentional quality while small, the craft and quality will start to evaporate, replaced by increased product ***complexity*** and ***tension*** between teams.

It is really hard to keep things simple, especially if you have a product that people really like. When you do things well, people will always ask you to do more. Your features will multiply and expand as you try to make them happy. Soon, new competitors will emerge that will tempt you to stretch your product in new directions. The more you say yes, the bigger and more complicated your product will become.

While I was at Facebook, this abstraction layer consisted mainly of data and metrics. Leadership would come up with goal metrics (Very Important Numbers) that loosely mapped to the current core business goals. If these metrics moved in the right direction (up and to the right) then it meant that the work you shipped made the product “better”! Your personal ability to move these metrics was referred to as your "Impact", and it was a major factor in assessing your job performance and salary (aka bonuses and promotions). This created a huge incentive to get very good at moving the important numbers. For the most part, the way you move these numbers is by shipping some kind of change to the product. In my experience, these changes tend to fall into one of three areas: **Innovate**, **Iterate**, or **Compete.**

Innovate > A major transformation like reimagining entire parts of a product, or making a whole new product. This means lots of exploration, experimentation, and uncertainty. It also requires alignment across many teams, which gets more difficult with scale. If you do get to ship, you may find that it can take time for people to adjust to big changes or adopt new behaviors, making short-term metrics look “concerning”. These kinds of projects seem to be more common at the start of a company, but become "too risky” over time.

Iterate > Smaller, more incremental changes to a product. You might be improving existing functionality, or expanding a feature in some obvious way. These projects are easier to execute than big, innovative projects, and they usually have a lower risk of bad metrics. At the same time, they also have a low chance of driving any meaningful user growth or impact because they’re not as flashy or exciting as new features.

Compete > Expand a product by borrowing features from a competitor that is semi-adjacent to what you already do. These projects are seen as "low risk" and sometimes “essential” because that competitor has already proven that people really want this feature. They have high short-term impact potential too, whether from the novelty effects of people trying something new or the excessive growth push (maybe a new tab or a big loud banner) requested by leadership to ensure that "our new bet is successful.”

Early at Instagram, I noticed a lot of value was placed on simplicity. One way that manifested was through a strong aversion to creating new surfaces. When you build a new surface, you force users to expand their mental model of your product. These new surfaces will also require additional entry points to help users find them. When you have a small product with plenty of room, this is an easy problem to manage. However, as the product grows and features multiply, internal competition for space intensifies. Top-level space becomes some of the most sought-after real estate in a product. Being on a high-traffic surface means tons of “free” exposure and engagement for your new surface.

Craft is simply more expensive at scale Companies with a small, talented team and a clear vision can easily produce high-quality products with a focus on craftsmanship, since everyone is motivated to do things well. As teams and companies grow, the cost of maintaining quality and craft increases exponentially, requiring more time and energy to keep things consistent. To keep “moving fast,” it's essential to allocate an equal number of people to focus on the foundational aspects that have brought the company to where it is now.

Define your values • Get as many people together as possible and write down/agree to the principles that drive your product decision making. It’s easier to push back on bad ideas when you can point to something in writing. • Find leadership buy-in at the highest level possible. Ideally your CEO or Founder, but if you are at a big company you may need to settle for a VP or Director.

Constantly push the vision • As a designer, you have the power to create very realistic looking glimpses into alternate futures. Dedicate some of your time to making some wild stuff that pushes the boundaries and reminds people that anything is possible.

Invest in relationships with collaborators • You can’t do anything by yourself, so spend time connecting and understanding the people you work with. Learn about what they care about, and share the same. Having a good relationship with your partners makes it less uncomfortable when you push back on bad ideas. It is a lot easier to say “no” to a friend, and then collaborate on something you can say “yes” to.

Most people think of demanding and supportive as opposite ends of a spectrum. You can either be tough or you can be nice. But the best leaders don’t choose. They are both highly demanding and highly supportive. They push you to new heights and they also have your back. What I’ve come to realize over time is that, far from being contradictory, being demanding and supportive are inextricably linked. It’s the way you are when you believe in someone more than they believe in themselves.

Researchers generally believe that creativity is a two-part process. The first is to generate candidate ideas and make novel connections between them, and the second is to narrow down to the most useful one. The generative step in this process is [divergent thinking](https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/divergent-thinking). It’s the ability to recall, associate, and combine a diverse set of information in novel ways to generate creative ideas. Convergent thinking takes into account goals and constraints to ensure that a given idea is *useful*. This part of the process typically follows divergent thinking and acts as a way to narrow in on a specific idea.

As a [memory moves](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-020-0064-y) from short-term to long-term storage, what’s represented in that memory is associated with existing memories (aka “[schemas](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166223612000197)”), and your overall understanding of the world shifts slightly. If information is related to what you already know, attaching it to an existing part of your schema helps you understand that information more quickly because you’ve already seen something like it before. For instance, after you read this article, what you know about creativity will have changed. The way memories are associated makes it possible to connect your ideas later.

Memories are the materials needed for creative thinking. Consuming [other people's ideas](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6870350/) in conversation by reading or listening to them (like you're doing now!) stimulates creativity and deepens existing associations. To widen our divergent thinking funnel, we could try and seek out new ideas that are maximally different from our own, but this typically won’t work. It’s actually better to make incremental steps outside your own filter bubble because new information [must overlap](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6870350/) somewhat with what you already know to be effectively associated and assimilated. Read voraciously and engage deeply with a wide variety of content to build a richer memory bank for you to tap.

Software that attempts to be different in a way that creates temporary excitement, but doesn’t create lasting value, is what I call “flavored software.” Of course, no one *thinks* this is what they’re building. They think their unique twist is a revolution, and that everyone will adopt their innovation in the future. But sadly, more often than not, they’ve invented the software equivalent of balsamic strawberry ice cream.

I don’t feel this security when I’m writing. I am intimidated by the clear and crisp writing of many people I admire. I am nervous that my good points will sound trite and my dumb points will be forever memorialized as dumb. I am afraid that my writing will make me sound stupid.

Historically, this feeling has resulted in me simply not writing. Or only doing so when I have to. When my kids say they are not good at something, I always respond with “How do we get better at things?”. It’s become such a common refrain that they now roll their eyes and groan when they give me back the answer, “Praaaactice.” But the repetition represents how strongly I believe this. In fact, if I could choose only one thing to instill in our children, it would not be curiosity. It would not even be kindness. It would be agency. I want them to know they are the captains of their own ships. This is why I ask them how they get better at things. This is why I tell them to practice. I want them to have the confidence and happiness that comes from the belief that you can solve your own problems.

One thing that challenged me was watching design decisions round out to the path of least resistance. Like a majestic river once carving through the mountains, now encountering the flat valley and melting into a delta. And the only problem with deltas is they just have no taste.

I’d argue that an organization’s taste is defined by the process and style in which they make design decisions. *What features belong in our product? Which prototype feels better? Do we need more iterations, or is this good enough?* Are these questions answered by tools? By a process? By a person? Those answers are the essence of *taste*. In other words, **an organization’s taste is the way the organization makes design decisions**. If the decisions are bold, opinionated, and cohesive — we tend to say the organization has taste. But if any of these are missing, we tend to label the entire organization as *lacking* taste.

When it comes to reading, you don’t need to finish what you start. Once you realize that you can quit bad books (or reading anything for that matter) without guilt, everything changes. Think of it this way: **All the time you spend reading a bad book comes at the expense of a good book.** Skim a lot of books. Read a few. Immediately re-read the best ones twice.

inkandswitch.com

Read 5 highlights

Writers often prefer to initially ideate in private and share the result with their collaborators later, when they are ready.

we found that our interviewees also had significant reservations about real-time collaboration. Several writers we talked to wanted a tool that would allow them to work in private, with no other collaborators reading their work in progress. Intermediate drafts aren’t always suitable to share, even with collaborators, and feedback on those drafts can be unwelcome or even embarrassing. In addition, some writers are troubled by the idea that their senior co-workers and management may be monitoring them – an unintended negative side effect of real-time collaboration.

Other writers reported putting their device into offline (airplane) mode to prevent their edits being shared while they worked.

Recently lots of people have been trying very hard to make large language models like ChatGPT into better *oracles*—when we ask them questions, we want the perfect answer. As an example, in my [last post](https://www.geoffreylitt.com/2023/01/29/fun-with-compositional-llms-querying-basketball-stats-with-gpt-3-statmuse-langchain.html), I explored some techniques for helping LLMs answer complex questions more reliably by coordinating multiple steps with external tools. I’ve been wondering, though, if this framing is missing a different opportunity. **What if we were to think of LLMs not as tools for answering questions, but as tools for *asking* us questions and inspiring our creativity?** Could they serve as on-demand conversation partners for helping us to develop our best thoughts? As a creative *muse*?

Recently lots of people have been trying very hard to make large language models like ChatGPT into better *oracles*—when we ask them questions, we want the perfect answer. As an example, in my [last post](https://www.geoffreylitt.com/2023/01/29/fun-with-compositional-llms-querying-basketball-stats-with-gpt-3-statmuse-langchain.html), I explored some techniques for helping LLMs answer complex questions more reliably by coordinating multiple steps with external tools. I’ve been wondering, though, if this framing is missing a different opportunity. **What if we were to think of LLMs not as tools for answering questions, but as tools for *asking* us questions and inspiring our creativity?** Could they serve as on-demand conversation partners for helping us to develop our best thoughts? As a creative *muse*?

Anne-Laure Le Cunff

Read 2 highlights

We confuse hard work for high-leverage work. These low-leverage tasks don’t meaningfully contribute to our success, and they certainly don’t contribute to our well-being.

Moving the needle may imply a corresponding level of hard work; which is not the case with high-leverage activities. This is the basic principle of leverage: using a lever amplifies your input to provide a greater output. Good levers work as energy multipliers. Instead of moving the needle, you want to operate the most efficient levers.

But pilots are still needed. Likewise, designers won’t be replaced; they’ll become operators of increasingly complicated AI-powered machines. New tools will enable designers to be more productive, designing applications and interfaces that can be implemented faster and with less bugs. These tools will expand our brains, helping us cover accessibility and usability concerns that previously took hours of effort from UX specialists and QA engineers.

• The universe is the “source” of all creativity. It is the source of an energy that we all tap into. • The universe pushes this energy as “data” toward the artist. It’s a cacophony of emotions, visual stimuli, and sounds that the artist stores in a “vessel.” • The artist develops a “filter” to determine what is allowed to reside in the vessel. • The work of an artist is to shape their life so they can get closer to the source. • They channel that source into something of personal value.

“The objective is not to learn to mimic greatness, but to calibrate our internal meter for greatness,” he writes. “So we can better make the thousands of choices that might ultimately lead to our own great work.”

A common problem with which I struggle as a creator is how much to participate in the discourse. Many people make their living by having the spiciest take on the news of the day, and sometimes I wonder if I would be better off being a larger participant in the culture. Again, Rubin has useful advice: “It’s helpful to view currents in the culture without feeling obligated to follow the direction of their flow. Instead, notice them in the same connected, detached way you might notice a warm wind. Let yourself move within it, yet not be *of* it.”

Perhaps the real magic of this book isn’t the advice itself. It is generic. It *is* anodyne. But maybe that’s the point. *The Creative Act* isn’t an advice book. It is artistic permission given in written form. What makes this book so magical is that he somehow translates his gift in the studio to the page. Rubin’s task is not to tell you how to create or how to act. His book gives you permission to be yourself. As he says, “No matter what tools you use to create, the true instrument is you.”

Keeping track of our thoughts in that regard can be tricky, but there’s a single principle which will absolutely make it easier: that of atomicity. A thought has to be graspable in one brief session, otherwise it might as well not be there at all. The way to achieve this is to ensure that there’s nothing else you can possibly take away from it: make it irreducible.

The killer feature is that wikis make it *trivially easy to break information into chunks*, by creating a new page at any time, and they then allow you (equally trivially) to refer to that information from anywhere. It is the inherent focus on decomposition and atomicity which makes a wiki — or any broadly similar structure, in terms of unrepeated and irreducible units of thought — so incredibly powerful.

• The Folgezettel technique realizes two things: Hierarchy and direct linking. This hierarchy, however, is meaningless. It is a hierarchy on paper only because you don’t file one Zettel as a true child under a true parent but just placing it at a place that seems fair enough because it is somehow related to his parent. • The Structure Zettel technique creates hierarchies. Direct linking is possible via unique identifiers. • You can replicate the Folgezettel technique with no loss of functionality with the Structure Zettel technique. • By using the Folgezettel technique, you create a single general hierarchy (enumerated, nested list) for your Zettelkasten. The same would be true if you create a Master Structure Zettel that entails all your Zettel.

If the single purpose of the Folgezettel, as stated by Luhmann, was to provide Zettel with an address, the time-based ID is not just good enough, it even is an improvement because it doesn’t need to introduce (meaningless) hierarchy and can be easily automated.

Folgezettel create one single hierarchy. Its meaning is minimized by the arbitrariness of the position: You can put a Zettel in one position or another. It is not important as long as you link from the other position to the Zettel. Structure Zettel on the other hand do not introduce one single hierarchy but *the possibility of indefinite hierarchies*. If there are indefinite hierarchies, the position of each hierarchy has zero importance to the individual Zettel. You can make it part of one hierarchy, or another, or both. You can even create new hierarchies. In this second difference lies the advantage in power of Structure Zettel over Folgezettel.

Instead of remembering individual Zettels, you would enter the Zettelkasten at a point that seems associated with the topic your are thinking about, then you’d follow the links. This is exactly how our own memory works: Mostly you don’t just recall what you memorized but surf through the associations until you are satisfied with what you loaded into your working memory.

There are two ways to get respect for your taste. The first is Rubin's way, where you have such a grasp on what you like that it influences how other people like it. The second is having a such pedigree in the work you've done in your craft that people respect your taste. As a designer and builder, the second one is your greatest power.

having taste can be the differentiator between what you make vs. an interface generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years, you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take a while. It’s normal to take a while. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

your taste will be the differentiator between you and other designers or software engineers in the craft of your work.

If you’re at a loss on how to develop taste, here are a few quick ideas of ways to practice: • Write as a form of critique. Whether it's about design aesthetics or delightful apps you’ve used recently, write about the attributes that connect it to the taste you have. You don’t even have to publish it. • Make mood boards of objects that have similar creative attributes. Can you find a piece of furniture that has similar aesthetics to a piece of hardware or software? • When listening to music you like, break down what makes you develop the taste. Is it the type of vocals, rhythm, lyrics, or something else?

Actually, one more note about making way too many icons for clients to choose from. To automate this a little bit, I set up a Photoshop document that had a smart object for the glyph, and a variety of backgrounds. This wasn’t necessarily anything we presented to our clients, but it was a great tool for us to see if any color or style jumped out as something we should explore further.

In 2023, the scene is very different. Best practices in *most* forms of software and services are commodified; we know, from a decade plus of market activity, what works for most people in a very broad range of contexts. Standardization is everywhere, and resources for the easy development of UIs abound. It’s often the case that what the executives or PMs or engineers are imagining for an interface is *fine*, perhaps 75% of where it could be if a designer labored over it, and in some cases more. It’s also the case that if a designer adds 15% to a design’s quality but increases cycle time substantially, is another cook in the kitchen, demands space for ideation or research, and so on, the trade-off will surely start to seem debatable to *many* leaders, and that’s ignoring FTE costs! We can be as offended by this as we want, but the truth is that the ten millionth B2B SaaS startup can probably validate or falsify product-market-fit without hiring Jony Ive and an entire team of specialists.

Indeed, even where better UIs or product designs are possible, we now deal with a market of users who have developed familiarity with the standards; that 15% “improvement” may in fact challenge users migrating or switching from other platforms, or even just learning to use your software having spent countless hours using other, unrelated software.

A well-designed mind map is an overview of the experience that a product team is going to offer to the end user, and this overview helps designers to keep track of the most critical aspects of the interaction (such as what users will try to do in an app).

Are you mapping a current state (how a product works currently) or the future state (how you want it to work in the future)? Depending on the answer, you will build your map based on the design hypothesis (if you’re mapping the future experience of the product) or user research (if you’re mapping the current experience).

There is a simple technique that can help you to find all possible scenarios of an interaction. Use the, “As a user, I want to [do something]” technique. “Do something” will describe the action, and this action will be a candidate for the nodes of your mind map. But, remember that you need to focus on user needs, not features of your product.

The central object can be a feature of your product that you want to learn more about, or a specific problem to solve. All other objects will be subtopics of that starting point.